Biology of Degenerative Disc Disease

The Biology of Degenerative Disc Disease

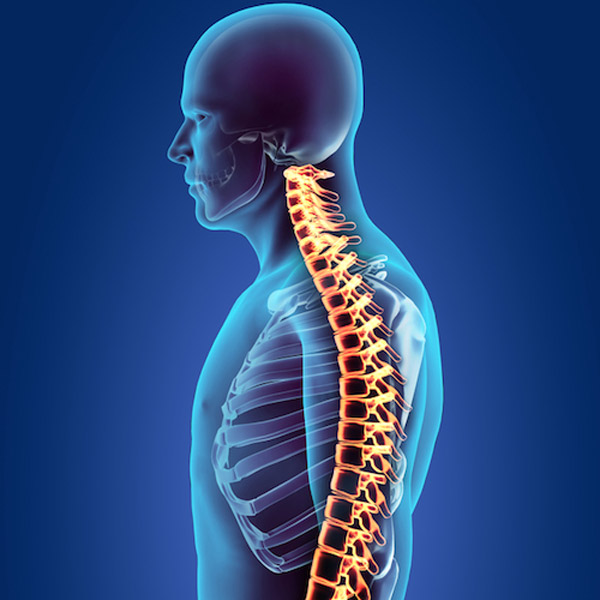

The degeneration of the intervertebral discs in our spine is considered a natural aging process. We’re the only animals on earth that walk in an upright stance. Unlike any other animal on earth, our spine is subjected to severe compressive forces every time we go into an upright stance. To maintain our head centered over our pelvis, our spine is forced into an S shape curve, with the lumbar spine being in lordosis, the thoracic spine kyphosis, and our cervical spine in lordosis. Looking at our spine from the side, it has the appearance of an S shape. Humans only began walking upright approximately 3 million years ago. In addition, up until the advent of antibiotics, most humans rarely lived past the age of 50. Thus, in a very short evolutionary period, our spines never developed the ability to avoid degeneration of our discs, and especially in patients or people older than 50. Thus, disc denegation is ubiquitous in humans over the age of 60.

Degenerative disc disease refers to symptoms of back or neck pain caused by wear-and-tear on a spinal disc.

Biology of a Disc

The spinal disc is the largest avascular structure in our bodies. This means it has no blood supply.

Despite this, it is a living structure that contains specialized cartilage cells. Nutrients to these cells must diffuse through the bones or vertebral bodies above and below the disc. Because it has no blood supply, the disc has minimal capacity to heal itself. Every time we get out of bed, we suggest our discs to biomechanical forces that cause progressive injury to the disc, especially the outer part.

The disc itself contains or consists of an outer annulus fibrosus, and an inner nucleus pulposus.

Think of the disc like a jelly-filled donut, where the donut or outer part of the disc contains collagen fibers that, under a microscope, appear very similar to a radial tire. This tough outer layer supports our disc and prevents excessive twisting. The inner part of the jelly-filled donut is the nuclear pulposus. What makes it like jelly is the fluid or hydration of the disc. The hallmark of degeneration of a disc is the loss of this fluid. This can be readily seen on an MRI scan, where the disc, instead of being white and juicy like a marshmallow, becomes black like a dried out piece of beef jerky.

What Is a Degenerated Disc?

Degenerative disc disease affects millions of Americans and results in billions of dollars in lost income in medical expenses annually. The exact cause of disc degeneration is complicated. Various animal studies have been contradictory in directly correlating biomechanical stress and disc degeneration. Likewise, human clinical studies have failed to link disc degeneration directly to mechanical factors. Disc degeneration on a cellular level is also complicated. As stated, nutrients must travel through the capillary network of the vertebral body and then diffuse through the end plate into the nucleus pulposus, or extra cellular matrix of the disc, to reach the actual cartilage cells. Thus, the disc itself is lacking in oxygen or hypoxic, and also is acidic. The end result is that as the disc degenerates, it becomes increasingly dehydrated and inflamed. The outer portion, the annulus, develops tears which often stimulates nerve fibers on the outer part of the disc that creates chronic back pain with any type of stress or motion.

As the disc loses its hydration, it begins to collapse, and this can be readily observed on an X-ray or an MRI scan showing a loss of disc height. This is the exact reason why humans, as they age, become shorter.

This same process occurs in the cervical spine. Symptoms in the lower back are stiffness, pain with range of motion or weight bearing. In the neck, this often creates pain in the neck, pain between the shoulder blades, headaches, and often radiating arm pain or leg pain from the back. As this process continues, the ligaments around the spine increase in size or hypertrophy and osteophytes form, the facet joints enlarge, and eventually the space for the nerves decreases, resulting in what’s called stenosis. Stenosis in the spine is often characterized by pain, weakness, or a change in nerve function in the legs or arms, typically during ambulation, or just standing in an upright posture.

Can DDD Get Worse?

Once you’ve been diagnosed with degenerative disc disease, the first question that may pop into your mind is, “Can my condition get worse?” As you age, the discs can continue to break down, you could experience more pain if you do not seek treatment. While health factors and everyday wear and tear are the two most prominent factors in DDD, you may be able to slow or reverse degenerative disc disease. Treatments such as stem cell therapy could help repair your discs and relieve the degenerative pain, ultimately stopping degeneration.

If you’ve been experiencing chronic back or neck pain and you’re concerned that you may have degenerative disc disease, make an appointment with the Elite Regenerative Stem Cell Specialists today. We’ll help you understand your condition and recommend the best course of treatment for your spine.